How can we overturn this prophecy?

On April 19th I was in Ouahigouya for the Farmers’ National Day. I visited the exhibition and stopped for a while at the stalls showing livestock from the northern region of Burkina. I was able to admire fine Goudali and Azawak bulls and some nice white sheep. But what surprised me most was that there was not a single Fulani livestock owner among the people exhibiting, a fact I found deeply disturbing. What could be the significance of this absence?

Two days later the “direct dialogue”between the President of Burkina Faso and farmers from the 13 regions of the country took place. There was no shortage of complaints. Among those related to pastoralists I noted: lack of access to water, lack of footpaths for animals, derelict dams, illegally occupied grazing land, recurrent conflicts between farmers and pastoralists, devastating effects of gold mining, pollution, lack of industries producing animal feed …”

Two days later the “direct dialogue”between the President of Burkina Faso and farmers from the 13 regions of the country took place. There was no shortage of complaints. Among those related to pastoralists I noted: lack of access to water, lack of footpaths for animals, derelict dams, illegally occupied grazing land, recurrent conflicts between farmers and pastoralists, devastating effects of gold mining, pollution, lack of industries producing animal feed …”

In addition I made some personal observations: the Fulani pastoralists are all too often regarded as “foreigners”, even when they have inhabited a given location for more than a hundred years. – In this month of April many dairies have a no or very little raw milk deliveries. Many get the raw milk from just a few “modern” cattle farms. - Industrial developers are allowed to continue their promotion of Jatropha cultivation, to the detriment of crops for human and animal consumption. – There are still a great many landless Fulani communities where (numerous) children are not sent to school. What will become of them, in light of the rapid population growth in Burkina? In 1965 (when I arrived here and the country was called Upper Volta) Burkina had 4 million inhabitants. Today there are more than 16 million. Nothing dramatic, on condition that the coexistence is organized and that territorial physical planning is respected. But if disputes between farmers and livestock herders are allowed to take a free course, the future might become sombre.

That is probably what one Burkinabè official had in mind when he remarked, the day after the Touareg rebellion in Mali:

“After the Touareg , it is the Fulani uprising waiting to happen in this region.”

I did already discuss this problem in a newsletter in January 2005: avec un article ayant pour titre : “Are we going to merely stand by and helplessly witness an ethnocide, or even genocide, of traditional pastoralists, the Fulani?

Since then the situation of these traditional herders has apparently not changed, even though it has become easier for them to sell their milk to local buyers.

However, it is the Fulani, taken as a group, that has changed. The process is slow (it started before 2005), but runs deep and could be a formidable asset for improving their conditions and for strengthening social peace.

The change will still have to be recognized and accepted.

What sort of change are we talking about? For decades (since before the independece?), Fulani communities have lived among themselves in isolation, not expecting anything (or very little) from the public administration and education system. That is why the report “Strategy for the planning, safeguarding and valuing of grazing land and equipment” from the Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources of August 2008 speaks of the local rank and file (that is the traditional pastoralists, the Fulani) as being “guilty of a wait and see attitude” (p. 38) when the State started to introduce “livestock zones”. But the report goes on: “at present they feel the need of such measures” and invites the communities to take initiatives and get involved in the necessary coordination and negotiation work. I am convinced that they are ready to do so.

What sort of change are we talking about? For decades (since before the independece?), Fulani communities have lived among themselves in isolation, not expecting anything (or very little) from the public administration and education system. That is why the report “Strategy for the planning, safeguarding and valuing of grazing land and equipment” from the Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources of August 2008 speaks of the local rank and file (that is the traditional pastoralists, the Fulani) as being “guilty of a wait and see attitude” (p. 38) when the State started to introduce “livestock zones”. But the report goes on: “at present they feel the need of such measures” and invites the communities to take initiatives and get involved in the necessary coordination and negotiation work. I am convinced that they are ready to do so.

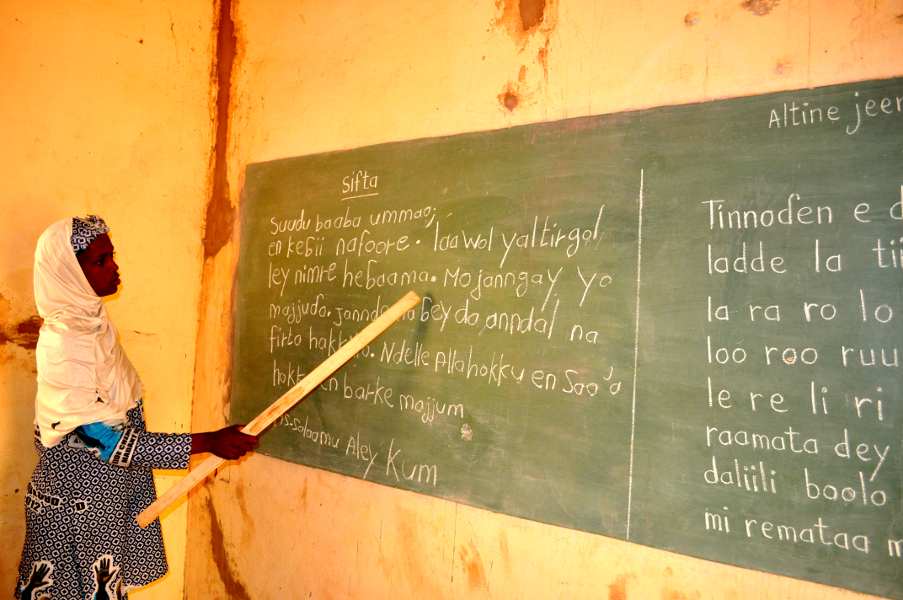

Another change is that the Fulani women have a strong ambition to learn to read and write in their native fulfuldé language. 6 years have now passed since we started offering them literacy courses in fulfuldé. The demand is not dwindling. At each visit we see that the women are in a majority in the classroom and attending diligently. This year we have even given financial support to two training centres set up exclusively for women.

S It often happens that at the end of a literacy course male participants will come up and say: “Now we must do all we can to have a seat on the Village Development Council (CVD, Cellule de base de la décentralisation - the local unit of decentralized public administration). .

Indeed the Fulani pastoralists have radically changed strategy, consciously or not. After having lived confined among themselves, they now endeavour to become fully recognized as citizens in their own right. And they are ready to take up their position in public life. Will we be able to take note of the change and draw the right conclusions?

“After the Touareg, it is the Fulani uprising waiting to happen in our region!”

What are we going to do invalidate this prophecy?

For my part I will make some proposals in my next newsletter, which may, I believe, overturn this prophecy.

Koudougou, May 1st 2012

Maurice Oudet

Director, SEDELAN